THE BEAST NARRATIVE

or the monsters we love

By Nikki Menig

|

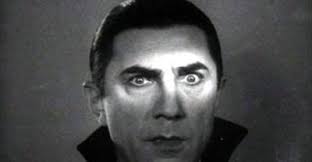

| He's got his eyes on her |

From the very beginning, there were monsters. And they did monstrous things that were scary and we, humans that is, kept our distance from them for both practical and religious reasons. But somewhere around the 1800’s humans and monsters began to meet. This was a cultural turning point and monsters started to become more human, and humans started to become more monstrous. The lines blurred and began to dissolve right in front of our eyes. Of course, it was all about love, it is always about love. So, what follows is without chronological logic or sense of generic development, but a series of striking moments in the history of man/monster love.

1946: Jean Cocteau Discovers the Beast

When it comes to man/monster love, no one goes as far as Jean Cocteau. His 1946 film La Belle et la Bête is a rift on everyone’s favorite abduction fairy tale. In Cocteau’s imagination, the beast is a beast, but also ridiculously human. Unlike most animals, he wears an overabundance of clothing, royal outfits that would put the most foppish of men to shame. He is the perfect example of the tremulous line between man and beast. In fact, except for Beauty, everyone in the movie is more of a beast than the Beast.

That’s not to say that the Beast doesn’t have his beast moment. He’s immature and arrogant, in spite of a charming, poetic nature. He so desperately wants Belle to favor him that he shies away from his animalistic nature, sometimes in surprisingly touching ways After he kills a deer and Belle catches him with its carcass, he is so mortified and upset that he literally starts to smoke. I don’t mean a cigarette; I mean his entire body starts to let off steam.

It’s so sad, yet it may be the kindest depiction of male violence ever seen. His allure is the vulnerability and heartache he feels in being a beast. The audience loves him because they love the person that they become around him. His honest pursuit of love is what wins us over. We empathize with it and are attracted by its grace. In the same way that an animal running is beautiful, the Beast trying to be romantic has the same heart-wrenching appeal. Cocteau shows that in love, the line between man and beast is barely visible.

The 1800s: Vampire’s Consume Us (Literally and Figuratively)

When we fall in love, sometimes we crave beasts that are, well, more beast. This is where Dracula enters the scene, revealing the suppressed depravity of the human soul. Bram Stoker’s 19th-century novel introduces us to what might be one of the most iconic figures of the imagination, the aristocratic killer who lives for and by the night, Dracula, Count Dracula. A beast in the guise of a debonair man, he is unencumbered by human ethics and morality and some of us, the innocent and pure Minna Harker for one, kind of like that.

Dracula is so animalistic that he literally controls them. Yet, one might say his greatest strength is that he’s a sophisticated man who is not ashamed of his carnal desires. He is always ready to transgress...something. With his sharp teeth and taste for blood, we can see him in every rock star from 1961 to 1971, the precursor to Jim Morrison, Mick Jagger, and the sneering glamour of early Punk. It is one of the most enduring archetypes of man/beast love that we have, and the one that keeps dealing out heavy doses of romance and tragedy.

In Stoker's original, we see the whole thing come to life. Dracula’s encounter with Lucy and Mina is every Victorian conservative’s nightmare. He transforms Lucy from a modest woman to a demon capable of things she never, ever imagined doing. And Stoker is clear that those things are of a sexual nature, the great unspeakable of the Victorian era. And when it comes to Mina, Dracula is willing to destroy anyone that gets in the way of his love, even if it is at the cost of Mina’s happiness and humanity.

|

| He'll do anything |

His love is destructive and detrimental, yet beautifully tragic. And this is what makes it so attractive because it is the textbook definition of what happens when we love. We can be destructive and we sometimes find that destructiveness to be attractive. It’s nice to have a monster so madly in love with you that he will rip out the throat of anyone who tries to get between the two of you. It’s a vicious love and has remained strangely attractive to the public since it first burst from the psyche of well-bred Victorian.

2008: Gender Roles between Monsters and Humans

Throughout most man/beast encounters, gender roles are rigid and defined Women are in distress and men are either monsters or saviors. That is why Tomas Alfredson’s 2008 film, Let the Right One In, is a breath of fresh air. Having a 12-year-old, girl vampire overturns generic conventions. Yet, it works incredibly well.

|

| Mayhem and a young woman |

Girls already feel like monsters at that age. For young women, this is the age the world sexualizes and preys on every weakness and so becoming a monster, she who terrorizes, is a nice change. Being or becoming the monster allows women to embrace a wilder sexuality and greater power. This taking on the identity of the monster is as empowering as it is terrifying. Eli, our female vampire, becomes the protector of Oskar, a shy boy who is bullied at school He is her ‘damsel’ and she is his monster. Oskar becomes enamored with Eli after he watches her attack and tear a man's throat out. And he falls even more in love when she shreds his bullies to pieces limb by limb in a school pool. Eli’s motives are unclear, but it is apparent she has a grateful and lovestruck male ingenue.

Eli’s motives towards Oskar are, to say the least, ambiguous. She does save him, but she is also saving him for herself. Not to eat, but to act as her human servant until he lives out his natural life, just like the man we assume is her father at the beginning of the film. It’s a relationship built on mutual trust and needs, but is also tainted with use and cunning. It is not romantic, nor is it a typical happy ending, but that is not what we are looking for when we go out with monsters, or become them.

2017: Making the Human/Monster Dynamic Work

One of the strangest questions of man/monster relationships is how come they never last? They almost all end in tragedy, with the beast’s hopes unrealized. Even the fairy tale ending of La Belle et la Bete only happens because the Beast turns into the bland Prince. When did the dynamic start to change? Did we want it to? Of course, we did, otherwise, we never would have said, why not?

My star and idol, Guillermo del Toro, takes these ideas and runs with them in his 2017 film, Shape of Water. One might say he even pushes a few of these ideas over the edge. His amphibian creature/star does beast-like things, such as eating the head of a cat. Unlike the beast, he feels no shame or particularly cares, it’s simply in his nature: he’s either hungry or just wants to have some fun. And our mute lead, Elisa, loves him regardless of this and may love him even more because of it.

The first interaction between them begins on common ground. Neither of them can talk. So, their courtship begins with a hard-boiled egg, slowly builds to music, and finally sign language. It is the wordless connection that makes the couple's fondness towards one another so alive. Del Toro understands that we don’t want niceties, we want the monster/human connection, romance, whatever you want to call it. He knows that in this exchange, we might want to be the monster, too. To overlook each other's differences and still pursue love is the true depiction of the Monster/lover romance that we crave.

The way the creature gently holds her hand when she points to the illustration of a friend on the card. The way he holds her when they’re in the water. It is here that we understand what we seek in our real-world relationships. We want to see the love put into action, no matter what, even when the loved one is fond of ripping cats’ heads off and eating them. We’ll overlook about anything for the right being.

Del Toro recognizes that real horror is within ourselves. The human heart is easily swayed and corrupted. It is not so much about appearance, which would be missing the point. We are too focused on the idea that Elisa falls in love with a large fish-man, and not that the creature brings normalcy to the horror that is human life. We know it is an unreasonable type of love, maybe we are even blinded by it, but we cannot ignore that we find solace in monsters that we cannot find with our own species. We know how far human darkness goes, as the monster teaches us how far romance goes.

Unlike most man/monster love, The Shape of Water has a happy ending. When the lovers escape from the government into the ocean, the audience could not be happier. Watching this movie feels like a sigh of relief. It gives us space to talk about trust, differences, sex, love, and fear of the future. Finally, a human/monster couple triumphs.

2013: The Need to See, and Be Seen (Hannibal TV Series)

Sometimes the difference between man and monster is not noticeable. Sometimes they are closer than we would like to think, wearing sheep - or in this instance - human clothing. What if the monster is simply nothing more than another person? Bryan Fuller's three-season, 42-episode, Hannibal, is a comedic yet beautifully tragic take on when a man is already a monster, finds one who understands him, invokes the monster within that person, then does whatever they can to stay in the other person’s life, even if the results are extremely destructive.

|

| A rare love between straight men? |

We admire monsters and murderers for the way they push against social conventions. On a basic level, they do not try to hide their true nature. We look for those who can truly understand us. Will and Hannibal constantly mess with each other because they like to see how much the other is willing to put up with. They would not be interested in each other without this game of cat and mouse. Fuller illustrates this by using typical romantic tropes. The affectionate nature of their relationship is in contrast to the brutality of their obsession with each other. They are constantly attempting to murder each other, from Will using other serial killers to try to kill Hannibal to Hannibal literally trying to crack open Will’s skull to eat his brain. While on the other hand, there are tender scenes, such as Hannibal tending to Will’s hands affectionately after he murdered a man - he was hallucinating the man was Hannibal, but that’s beside the point in Fuller’s world. You might ask why they continue to taunt each other. Their love is manipulative and yet strangely alluring.

The fans, and even the actors, desperately want the relationship between Hannibal and Will to what should we say, go all the way? However Fuller views their relationship differently. His main goal is to portray romance and devotion in a non-sexualized way, straight man to straight men. However, this line becomes blurry as the show progresses, making the Fuller’s notion of platonic romance seem more of a dodge to get past NBC’s censors. So, are we underestimating Fuller’s writing and understanding of love? Maybe what people are saying is “Look, I am damaged and I like seeing other damaged people falling in love, especially with a damaged villain.” Perhaps Fuller does not fully understand the genius of his work. Or maybe he does and just doesn’t want to say so, which, in its way, is kind of beastly.

What he does do is take these incredibly attractive actors and maims them both mentally and physically, then says- “Aren’t they beautiful?” And you are forced to say yes.

Conclusion

So here we are, monsters and humans, staring down a divide that we do not accept. We love monsters because we feel monstrous. We understand the horror of evil because we see it within ourselves. So, loving a monster gives us the comfort in finally being known. We all have a dark side and we fear it, not because of its nature, but because others may see it and cry murder. Monsters embrace this side, are tormented by it, or both, and we can empathize. We see ourselves in them, and cannot help but fall in love. For we wish to love that side of ourselves, and for others to look fondly upon it. Besides, monsters and their love anchor us to our humanity. At other times, it’s just nice having a beast love you and only you.

©Nikki Menig and the CCA Arts Review

No comments:

Post a Comment