REASSESSING THE GREAT Yoko Ono

or the unfairness of being John Lennon's wife

by Gordon Fung

|

| Yes, she can sing |

“Yes, I'm a witch, I'm a bitch/ I don't care what you say/ My voice is real, my voice is truth / I don't fit in your ways.” In, “Yes, I’m a Witch” (1974), Yoko Ono directly confronts her outsized and complex public persona. She clearly cares about the unjust accusations of breaking up the Beatles and the sense that she’s more of a supernatural cipher than a real person. What’s clear is that what matters to her is her voice, both her actual voice and its symbolic potential, and what it can accomplish. Ono is infamous for her screaming. In Voice Piece for Soprano (1961) revived in 2010 for her New York retrospective, the MoMa staff and museum visitors were continually unnerved as people took her up on the challenge of joining in on the screaming. This torture lasted five months.

|

| Oh no, the pain, the pain! |

Her reputation for screaming earned her a pop cultural place in a Family Guy gag (S16, E17), where Brian the Dog asks Alexa “What is love,” and everyone’s favorite computer buddy downloaded and played the whole of Ono’s work. Not only does the general public hold Ono responsible for breaking up the Beatles, but the going take is that her music is pointless, crass, and on the level of a toddler throwing a tantrum. But what is missing here, is that most of the listeners have misjudged Ono’s works, especially neglecting her classical training and work as a conceptual artist.

Ono’s Early Conceptual Works

Prior to her relationship with Lennon, Ono was devoted to and a product of the conceptual art of the early 1960’s. Like her above-mentioned “screaming” work, she carried out a number of instructional pieces that challenge the relationship between artist and viewer. For example, Painting to be Stepped On (1960) instructs the viewer to “leave a piece of canvas or finished painting on the floor or in the street”; Painting for the Wind (1961) instructs the viewer to “make a hole. Leave it in the wind”; Painting for the Skies (1962) instructs the viewer to “drill a hole in the sky, cut out a paper the same size as the hole. Burn the paper. The sky should be pure blue.” These ideas, the lynch-pin of conceptual art, challenged the norms of high-art while being definitively high art.

|

| Ono, the Villain |

Ono’s conceptual work had roots in the Dadaists of the early 20th century and possesses a humor we rarely associate with her public image as the Beatle Buster. In her Map Piece (1964), she instructs us to “draw a map to get lost.” The whole collection of instructions is available in the book Grapefruit, which was originally published in 1964 in a limited edition and reprinted for a mass market in 1970 and 2000. Most of these instructions are purely conceptual and are impossible to be carried out—not atypical of dadist art.

In 1964, Ono pushed the boundaries of her work even further with Cut Piece which premiered in Yamaichi Concert Hall, Kyoto. In it, Ono sat still and silent on stage and invited people to use a pair of scissors to cut a portion of her clothing and take it. The subsequent performances in New York and London in 1965–66 drew critical attention. We should also note that Ono’s work preceded Marina Abramović’s controversial performances by as many as ten years.

|

| Quite a cut up |

Disavowing artistic value through concepts, humor, and shock are crucial to Ono’s early work; as part of the Fluxus group, Ono was acquainted with John Cage by the late 1950s. Recalling Cage’s influence, Ono told Hans Ulrich Obrist that “what Cage gave me was a confidence that the direction I was going in was not crazy. It was accepted in the world called “the avant-garde.” What I was doing was an acceptable form. That was an eye-opener for me.” What’s fascinating about Ono’s career before the Beatles is how entrenched she is in the culture and controversies of the avant-garde.

Encountering John Lennon

Ono first met Lennon at the Indica Gallery in London on November 9, 1966. John Dunbar, the gallery owner, had invited Lennon for a preview of the show. Lennon walked around the gallery, taking in the show and started playing around with some of the art, which is what the art asks for but was somewhat rude considering the circumstances. Ono didn’t like that and that sparked a discussion, and as we all know disagreement can often lead to love. This is the beginning of the romance between one of the world’s, maybe the world’s biggest pop star at the time, and an avant-garde something.

|

| Avant-Garde Pop |

Lennon was not enthusiastic about art and especially the conceptual wing of the avant-garde, but he was deeply impressed and amused by Ono’s humor and daring. One of the pieces he saw that night was Apple (1966), which is an apple displayed on a plexiglass pedestal with a brass plaque that says “APPLE.” To reciprocate Ono’s playfulness, Lennon took a bite out of her work and after that bit of fun, attempted to “nail down” one of Ono’s paintings, Painting to Hammer a Nail (1961). It was another of her “instruction paintings” designed to undermined the artist's authority, although Lennon was taking it a bit far. His insouciance irritated her at first. Lennon, in an interview with Rolling Stone in 1980, recalled that “there was this little conference and she finally said, ‘Okay, you can hammer a nail in for five shillings [60 cents].’ So smart-ass here says, ‘Well, I’ll give you an imaginary five shillings and hammer an imaginary nail in.’ And that’s when we really met. That’s when we locked eyes, and she got it and I got it, and that was it.”

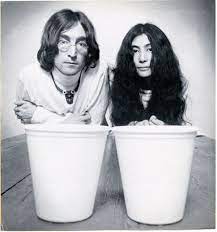

Ono and Lennon’s Three Experimental Albums

Soon thereafter, Ono and Lennon began their romantic relationship, likely around May of 68, though both of them were married at the time. While Lennon’s wife Cynthia was on vacation in Greece, Lennon invited Ono to his home studio. Besides the romance bit, they recorded Unfinished Music No. 1: Two Virgins (1968), their first collaborative album during a whole night session of musical experimentation. This unconventional title surely would barely register in avant-garde circles, but for pop music lovers even the title was a shocker, especially from the man who gave the world, “I Want to Hold Your Hand.” The weirdness continued onto the album cover, which shows Ono and Lennon naked and, well, naked. This controversial image deterred the parent record company EMI from distributing it. Solving the problem, the album was sold in a brown paper bag.

|

| Time for a brown bag? |

The shock didn’t stop there. Lennon and Ono’s album is not unlike tape music, Edgard Varèse’s musique concrete, John Cage, or even Iannis Xenakis’s. What shocked the world was not Ono’s craziness, but Lennon’s involvement. Lennon’s appetite for this type of avant-garde music production was at odds with his public image. The tracks were full of noises: Lennon’s whistling, Ono’s wailing, unknown scratch sounds, random strumming and glissandi on electric guitar, even some occasional chordal playing on piano. If one thinks that the Beatles were adventurous in experimenting with back-masking and overdubbing, among other recording techniques in the late 60s albums, try listening to this album. You won’t regret it (or you will).

Succeeding their first experimental collaboration, Lennon and Ono recorded Unfinished Music No. 2: Life with the Lions six months later (recorded in November 1968, released in May 1969), while Lennon finalized the divorce with Cynthia. The couple wed next year in Gibraltar on March 20, 1969. They recorded Wedding Album in March and April of 1969 (released October 1969), their third and final experimental album. The second side “Amsterdam” was recorded during their honeymoon. It mainly consists of interview conversations, and captured sounds during the Bed-ins for Peace project. Bed-ins were a nonviolent anti-war protest that called for world peace in order to stop the Vietnam War.

|

| A Bed-In for Peace |

After their honeymoon and protest, they returned to London and recorded the first side of Wedding Album. It is called "John & Yoko.” The intimacy of the title would seem to promise some romantic and passionate story-telling. The twenty-minute-long track offered something else. It begins with Lennon calling Ono and Ono calling Lennon back. This interactive reciprocity — of calling, shouting, screaming, whispering, moaning, exhaling the lover’s name — is heard in various intensities, moods, and tempo, over the recording of their heartbeats. If you were part of the contemporary music or art scene, this was kind of standard fare, but for Lennon fans, even the fans of “I am the Walrus,” this was difficult to get a hold of.

Lennon obviously did not care about what people said about his private life, but he did care about the boss in the music industry, namely the ratings, and so the couple turned their work down a notch or two. In 1969, they founded the Plastic Ono Band and focused on producing more approachable songs, some of which proved that Ono could actually sing. When the Beatles officially broke up the following year, disheartened fans looked at the Plastic Ono Band and Ono, and accused her of destroying the greatest band in the world, ever.

Ono and the Plastic Ono Band

The Plastic Ono Band became the backbone of Ono and Lennon’s solo and collaborative projects in the early 70s. The debut albums were Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band (1970) and John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band (1970). Lennon, obviously had had enough of all the wild experimentation and returned to his version of pop music daring. Ono, though, kept to her radical inclinations. In the song “Why” (1970), the track begins with a steady drumbeat and groovy baseline over some reverb, not unlikely any catchy rock music at that time. And then Ono begins wailing the song’s one line — “WHY” — with, well, you just have to listen to it yourself. It’s indescribable. That said, Ono’s vocal techniques in “WHY” are demanding and require an incredible amount of control. These screams are not easy to imitate or mock — even if many have tried.

Message of World Peace and Feminism

Approximately Infinite Universe (1973) was Ono’s first real departure from the avant-garde. These more commercial albums definitively prove that she can sing and with an uncanny sense of pitch. Her vocal range is wide. She can handle the lower end of an alto, while hitting the high notes of a coloratura soprano with ease—according to a forum post on the range planet, Ono sings in a range from B2 to F6, and at least three octaves are in her sweet spot.

|

| She screams |

With the ending of Vietnam War in 1973, Ono turned her attention to feminist messages: “Sisters, O Sisters” (1972), “Woman Power” (1973), and “What a Bastard the World Is (1973). In one song, you can sense Lennon defending Ono: “We insult her every day on TV/ And wonder why she has no guts or confidence/ When she's young we kill her will to be free/ While telling her not to be so smart we put her down for being so dumb… Woman is the slave to the slaves/ Yes she is,/ if you believe me,/ you better scream about it.”

This call to “scream about it” is like a wake-up call for us to examine more closely why Ono screams while she can sing in the first place. Ono was raised in a wealthy Japanese family, and she received training in Lieder singing and piano when young. East Asian upbringing commonly instructs females to be obedient and submissive; especially among a family as financially successful as Ono’s. Ono’s deliberate subversion of proper singing is not only an aesthetic, but a manifesto declaring herself free of the rules of patriarchal domination.

©Gordon Fung and the CCA Arts Review

No comments:

Post a Comment