YE, A BEAUTIFUL DARK TWISTED LEGACY

Or, how the artist's life reflects the rhythms of his work

By Lewi Thute

The debate over separating art from the artist has persisted for centuries, gaining even greater significance in today’s social and cultural climate of cancellation. No single artist, or personality, has put this argument to the test more than Ye, formally known as Kanye West. His career and life are interlocked in a crazy duet and has become increasingly unstable as each chapter of his life progresses. Due to this, many current and long-time fans defensively argue that we must separate Ye from his art to preserve his incredible work. I say, no. Ye’s life is his art and to try to separate the two is to strip his art of all meaning, no matter how problematic his behavior is.

Ye has released eleven solo studio albums, and each follows a recurring pattern: public outburst, the music’s release, a retreat from the public, and kind of, maybe, not really, an apology. Sometimes the apology is the album; sometimes the album is the outburst, although the outburst is rarely an apology. This has held true from his debut to his latest work, 20 years later. Whenever he’s working on an album, you count on an essential level of provocation, ranging from egotistical tirades, radical declarations, and bizarre calls out to people who would rather be left out of it altogether (Hello, Beyonce). However, the type of outburst, its content and its form are intimately connected to the music that precedes or follows it. Soon after, Ye withdraws himself, apologizes, and then the whole thing starts again.

The tension between Ye’s vision and public expectations is a major source of this cycle. His ideas often clash with social norms, shocking expectations. This divide was evident during the rollout of Yeezus (2013) , his sixth studio album. Despite its critical acclaim, the album sparked mixed reactions, partly due to critics’ concerns that Ye was too focused on his fashion career, causing some to dismiss the album as a “wasted” effort. The album was also publicly mocked by industry insiders as his work in fashion was derided by fashion elites. And all these criticisms of his views and ambitions feed into the album's core attribute—a rebellion against establishments—and his life, not surprisingly, mimicked all of it.

Of course, the pattern had been well set by then. Ye’s first noted outburst was at the American Music Awards in 2005. It was after his debut album College Dropout (2004) lost and he bitterly said that his loss at the American Music Award was a robbery. Ye later takes back this statement, stating "I was raised better than that. It was very ignorant." Notice how he appears to apologize, but really doesn't. All he’s saying is that he was raised better than to say what he actually believes; it’s clear that he isn’t taking any of it back.

This little incident marks the beginning of Ye’s pattern of outbursts and retreat. A year later, just a month before the drop of his second album Late Registration (2005), Ye, while performing at a Live 8 Benefit concert, said that “AIDS was a man-made disease [that was] placed in Africa just like crack was placed in the black community to break up the Black Panthers.” He later doubled down on these comments after the album's release in the song, “Heard ‘Em Say”, with a bar that alludes to AIDS being a manufactured virus. Here is an example of the outburst and the music fusing. It’s clear that the opinions in “Heard 'em Say” were percolating for a long time. But what’s interesting is that the AIDs comments weren’t too far out of the public swim and it wasn’t the only outburst related to Late Registration.

|

| You never know what he's going to say |

While on a TV broadcast benefit concert for Hurricane Katrina, Ye claimed that George Bush didn’t care about black people. This outburst was met with less criticism, as it fit into the political landscape of the time– acting as both the outburst and the retreat. Many people had the same opinion, regarding the government’s relationship with the black community. Not to the same extent, but the core feelings behind his statement were in alignment with many of his fans. These themes of race, socio-economic struggle, and fame are present in a few of his songs. Tracks like "Heard 'Em Say" and "Crack Music" highlight issues of systemic racism, poverty, and inequality. Ye was about twelve years ahead of the systemic racism argument going mainstream. His reflections on the Black experience in America, highlights an important detail – he speaks for a select group of people. Sometimes it works in his favor and sometimes it certainly does not. This era of outbursts and withdrawals was tame, but marked the foundation for everything Ye does going forward.

|

| Mother and son |

With the release of 808s and Heartbreaks (2008), Ye’s art started to evolve and intertwine with his life. As a result, his outbursts became more aggressive. A year before the album’s release Kanye’s life took an unexpected turn. Donda West, his mother, passed away. Days after in a live performance Kanye broke down while singing about his late mother. And in the following months, he and his ex-fiance Amber Rose separated. What we didn’t know was that Ye’s adherence to Black Panther's ideals also died with his mother. Severing the connection to his mother’s beliefs and commitments, her death changes the trajectory of his albums and his life going forward. Starting with 808s Ye took an open and experimental approach to hip-hop with many of the tracks revolving around themes of vulnerability. The initial reaction to his new approach to hip-hop wasn’t great, but, more importantly, we had no idea what sort of outbursts it all would lead to.

At the 2009 MTV Video Music Awards, Ye stormed onto the stage as Taylor Swift was giving her acceptance speech for Best Female Video claiming that Beyonce deserved it. This incident sparked media outrage everywhere. At the time this was his most controversial incident and led Ye to exile himself from the public eye, escaping to Oahu, Hawaii for the better part of a year before coming back with an album that was the apology.

Ye returned with the highly esteemed album My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy (2010), which was immediately praised and appreciated by critics and the public alike, winning multiple Grammys for it. In addition, Ye made a short film before the album’s launch titled Runaway that was met with the same praise and love as the album. This whole era was his longest period of reflection and retreat. From the music to his public proclamations, all of it was crafted to be accepted by the industry that shunned him, but as usual the pattern persisted and you could feel some of that bottled up tension during his tours. At both Coachella and a concert in Melbourne, Australia – at the end of his set - Ye performed different versions of “Runaway”. In the outro of the song, he directly addresses his previous actions and wrongdoings, but in a derogatory way, often calling himself the asshole and making a vulnerable call out to his ex-fiance. Although, this era as a whole worked as an apology, notice how he doesn’t actually apologize to his ex but rather just tears himself down; almost as if he is apologizing to himself and not her or anyone in particular.

Whatever the case, after the VMA incident, Ye turned himself into the acceptable Kanye West. In the years from 2009 to 2011 after the release of the MBDTF, he was relatively unproblematic and subdued, but as the pattern proves, he's about to unravel once again. With the back-to-back album releases between 2016 and 2021, Ye’s music starts to mimic his life a lot more. The Life of Pablo (2016), Ye (2018), Jesus is King (2019) and Donda (2021) demonstrate the intimate relationship between Ye’s creative life and his personal demons.

While Pablo was in development, Ye’s life was fairly tranquil. His family, his fashion career and his faith had found some degree of stability. Days before the release of Pablo, Ye tweeted ‘BILL COSBY IS INNOCENT’. You can probably imagine what the public response was… they were outraged. This outburst had neither a crescendo nor a conclusion, it just ended and then was followed up by Pablo’s release. Many people believed that it was a marketing ploy. I believe that this outburst just set the stage for the album's concerns: faith, fame, love, family, and the artist’s internal conflicts. The gospel elements in Pablo often addressed various notions of redemption. The opening track "Ultralight Beam" is an obvious example. The ending track “Saint Pablo” takes on a rather different view on redemption. Invoking Saint Paul (Pablo in Spanish), Ye uses Paul’s life to highlight his own desire to be a voice of truth while grappling with his own sacrifices. However, this ‘voice of truth’ becomes a distorted reflection of himself on his Pablo tours.

|

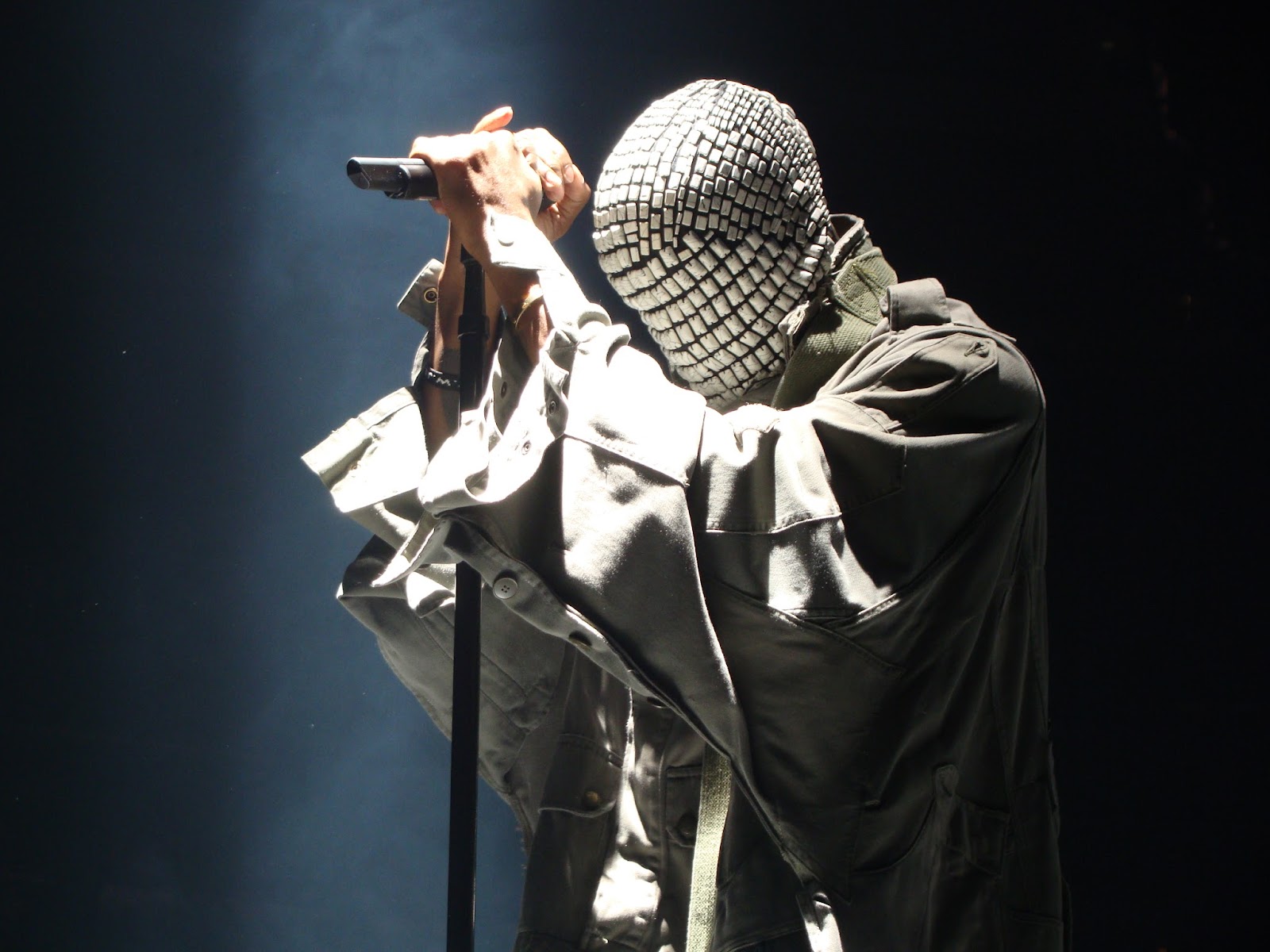

| Whatever the message, Ye has it |

The Life of Pablo tours were full of rants against the music industry, against fellow artists and a full-throated endorsement of then-presidential-candidate Donald Trump. At one show, Ye even arrived an hour late and cut the performance short—an abrupt end that some attributed to his hospitalization a day later for exhaustion and sleep deprivation. With this, he then canceled the remainder of his tour and left the spotlight. I suspect, however, that this moment marked a larger transformation in Ye’s mental state and public persona, a shift that would continue to shape his future projects and public image.

|

| Family life for a bit |

Ye is bipolar. At this point, his diagnosis is synonymous with him. He shared his diagnosis on YE (2018), in which he blatantly states “I Hate being Bipolar – It’s Awesome.” The album’s cover art, much like his retreat to Hawaii in 2009, Ye dismissed himself from the public eye for two years in Wyoming, working on various musical projects in an era now dubbed the Wyoming Sessions. It began another era of reflection and reinvention. But unlike Ye’s return from the MBDTF retreat which was followed by more reflection, this time his outbursts were even crazier. Exactly a month before YE released, in a live interview with TMZ, Ye said the one thing you wouldn’t expect an African-American to say: “Slavery was a choice”. As you can expect everyone was outraged – he was even confronted live in that very interview by a producer at TMZ, Van Lathan. Although Ye doesn’t explicitly apologize, he reframes his previous stance in a more vague, neutral way. This tone, in hindsight, appears as a reflection of the album itself, which offers a darker take on Ye’s usual themes of fame, love and self-image. This album isn’t an apology, but an acceptance and acknowledgement. Here he is unfiltered and embodies a version of himself, we could call it a persona, that is both self-aware and unapologetically flawed.

By acknowledging how his actions impact his family, Ye enters an era of tranquility and immerses himself in Christianity for the next few years. Ye’s family was thriving, his fashion career was successful and he’d declared his commitment to his faith which influenced his 9th studio album Jesus Is King (2019). Going on to condemn premarital sex and his wife Kim Kardashian’s fashion choices, which is ironic, given how Ye treats his new wife like a sexualized mannequin.

What we might call the Donda era marks a major turning point for Ye, which reaches its crisis point in 2021 with his divorce from Kardashian. This moment fuses his artistic and personal life, yet again. While developing Donda, his tenth studio album, Ye hosted three high-profile listening parties, each revealing the album at different stages. Like Jesus is King, Donda centers on themes of faith, loss, and redemption, but also revisits the personal turmoil reflected in YE (2018).

|

| That's a look |

Ye’s life at this point didn’t just mimic his art; it becomes his art. He legally changed his name from Kanye West to Ye, embracing his public persona entirely, and the music became his final outlet. Like years before, in a raw, emotional performance at the Larry Hoover Benefit concert (2022), he dedicated a rendition of “Runaway” to Kim—his final public oasis before the controversy of his anti-Semitic remarks in the months that followed. Ye’s life and music are inseparable, forming a cycle of personal and artistic evolution that consistently intertwines the two. Time and time again, we see how Ye acts and reacts in this push-pull manner: public outbursts often precede a period of social retreat, where he reflects, reinvents, and ultimately channels those thoughts into a new era of music. As a result, Ye’s music cannot be fully understood without the context of his life—and vice versa.

Ye’s life and art are intertwined. We know this. But as an audience, we must separate ourselves from him to truly appreciate his work. His art is a reflection of his personal highs and lows—sometimes brilliant, sometimes deeply controversial. Engaging with Ye's music while separating ourselves from his public outburst allows us to view his work without being fixed to it. To truly appreciate Ye’s music, we must acknowledge the person behind it but also avoid letting his controversies define our relationship to his work. We cannot separate the art from its artist but we can separate ourselves from the two.

©Lewi Thute and the CCA Arts Review

No comments:

Post a Comment