THE HYBRID LIFE OF THE MEXICAN SOUL

or that's a lot of culture for one mind

By Renata Blanco

Sometimes I feel as if I only have fragments of Mexico in my soul, bits and pieces of ideas, beliefs, visions all playing around in my mind. And then I think, well, that’s what it means to be Mexican. When I was young, as an only child and grandchild, I was extremely spoiled. Every October for my birthday I would ask my grandmother for Pan de Muerto (Day of the Dead bread). I share with many Mexicans, the troubling trait of undoing the line between death and birth. As my grandmother would explain, Pan de Muerto is a piece of culinary magic, a traditional dish born of wildly different cultures, a combination of ingredients from everywhere that somehow becomes in our crazy nation, just bread. I’m not sure whether to honor it or cry.

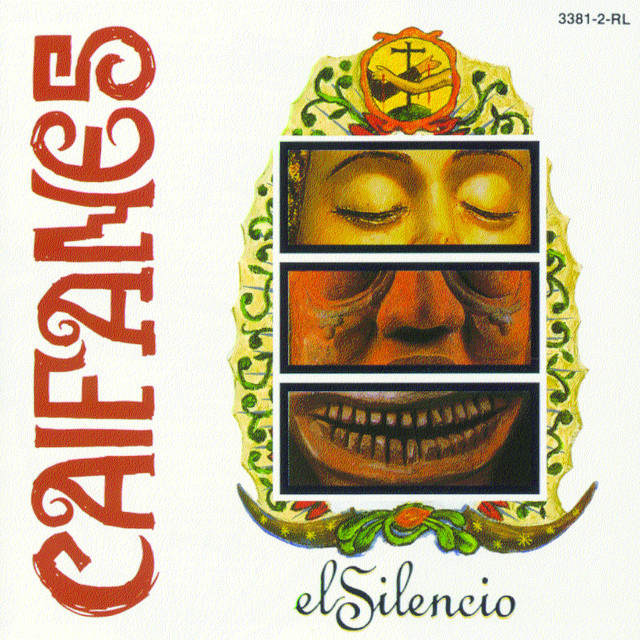

Oh, you’re still reading. Let me try starting again. If someone put a gun to my head and said, “Give me one image and only one image that symbolizes the poor, sad, glorious plight of Mexican identity, luckily for me I wouldn’t die, but whip out Caifanes’ 1992 album, El Silencio, and say, “Don’t shoot, look at this, I have done what you asked!” And when they would look at the album cover, baffled and still threatening, because they are not Mexican, I would begin this interpretation.

|

| This beautiful cover once again |

Let’s get the boring part out of the way, my gun-toting American friend, look at the right side of the cover where even you can see the name of the band spelled vertically in red bold letters. As with the geometric shapes in pyramid walls, the font transports us to the pre-Hispanic era, approximately between 900 A.D. and 1521 A.D. The red letters have essentially the same geometric pattern and shape we see carved and sometimes painted in Aztec pyramid ruins. It feels as if a portal in time is opening to help us remember all that has been with all that is.

Now that the font is out of the way, let’s look at the image, a triptych. It might not be obvious, but there’s a huge difference between two and three. When you have twins it is easy to keep an eye on both, but triplets mean total chaos, and that is Mexican identity, a hard to rest your eyes on triptych that includes the Aztec empire, tears, and the good Virgin Mary. Let´s take a look at the cover once again.

It is no secret that Mexicans are obsessed with death, we have two whole days to celebrate it every year, November 1st and 2nd. For centuries that eerie smile at the bottom panel has leered at us in codices, statues, and trees of life, belonging to the one and only master of the dead, Mictlantecuhtli. For those of you who need to know how to pronounce the name of the master of the dead, click on this link. He is not only a representation of our big post-mortem traditions, but also a connection to our most ancient heritage, the Aztec empire. Which is like Mictlantecuhtli, dead. But both are still an unescapable presence, shining through whenever we eat a good Mole, walk past Templo Mayor, or even speak names and words that are unpronounceable to all foreigners.

Let’s take a look at the next image of the triptych and remind you that for Mexicans there never is a good reason to cry, or at least that’s what our mothers tell us. But looking at the second image, we can see tear-stained cheeks and actual tears; tears that mourn something lost. Like when you look at yourself in the mirror and know something is missing, it might be the rest of a face, a hair piece, some false teeth, but you need it, just as we need glue to hold our identity together. But it’s not there, so we pull on our hair and cry in frustration, because we’re wearing an outfit that’s not right and it’s too late to change. Our identity is not complete, but it is what we have to work with.

The final image of the triptych is of a wood carving of the Virgin Mary and you don´t have a Mexican soul without the Virgin. Her eyes are closed, as is always the case. She´s blond, quite common for Mexican Virgin Marys, but maybe not appropriate for such a dark-haired country. She is, of course, a European import and, kind of, in a strange, we are, too. She´s sad and that’s the way we like her. In a way it brings us closer to the spirit of her. She is at the same time of us and foreign to us and her placement on the cover as the third and last image catches the schism at the heart of our identity. We are not quite, but part of.

|

| Almost as good as the Virgin |

But before the Virgin there was another lovely woman that haunted people’s minds. La Llorona, yes, she is probably one of the oldest urban legends in the country, but she is also a song. A song that was born a poem, as most songs are. Confusingly enough, she is a love song, one that asks why she cries all the time. The music for this song came on a boat. But the feelings and the words were here long before. Even though the melody has stayed the same throughout the years, the words have not, not even the language has stayed the same. What might have been once sung in Zapotec, is now sung in Spanish. It is always sung differently, but the chorus stays the same, as do the feelings. And there are always feelings.

I became La Llorona when I watched the folkloric dance performance at Palacio de Bellas Artes. I sobbed. I can’t tell you why, but I just did. Sure, the show is beautiful, but there is more to it. My eyes were truly opened the second time I saw it, maybe because they were not blurry with tears. I could see that the show is as far from a ballet as you can get while still being able to call it one and present it at The Palace of Fine Arts: Bellas Artes. The producers market the show in such a way that the posh people in Mexico will willingly go to a folk dance because it has been turned into high art with highly trained dancers. What could be more Mexican, to take a folk act and turn into a ballet just so people will feel that it´s okay. The show is a surreal and vague overview of different elements of Mexican history, mixed with daily life events. There’s everything from pre-Hispanic music to waltz, son jarocho. The diversity of the choreography, the costumes that combine western fashion with traditional elements, and the ballet that is not a ballet can make any little girl cry, especially if she’s Mexican.

The way the ballet dances through time is the same way Octavio Paz traces the conflicts of Mexican history in his poem, "El Cántaro Roto." That proves that when we tell stories of our past, everything spills out. The way in which Paz travels throughout Mexican history is like a flash, everything goes by so quick that there is no space to settle down and we Mexicans read the poem wondering where exactly we lost our grip on identity. The poem starts with the phrase “La mirada interior se despliega y un mundo de vertigo y llama nace bajo la frente del que // sueña” (the interior look is unfolded and a world of vertigo and flame is born inside the forehead of those who dream) This phrase as complicated and long as it is, is just telling us about someone who is reflecting on how Mexico is now what it is (as most Mexicans do at least once a week). Something that I have not even thought about, but clearly Literature Noble Prize winner Octavio Paz has, is how important nature and landscape is to the construction of Mexico as an image and identity. His poem starts with beautiful and lush descriptions of the amazing Mexican landscapes. But as we transition into the second stanza everything changes, the poem takes a dark turn and suddenly the beautiful landscapes turn into a battlefield.

The history of the Mexican conquest intermingles with the descriptions of the landscape “caballo, cometa, cohete que se clava justo en el corazón de la noche” (horse, commet, rocket that pierces the heart of night). Now, as cliché as it might be, the landscape represents the mood and unrest of colonial times, and Paz gives us dry, boring, desert landscapes instead of the colorful and vivid ones. And let’s not forget how the first piece of our identity was covered by the second piece, the European import. We also get some direct references to this “El dios-maíz, el dios-flor, el dios-agua, el dios-sangre, la Virgen, // ¿Todos se han muerto, se han ido, cántaros rotos al borde de la fuente cegada?” (The corn-god, the flower-god, the water-god, the blood-god, the Virgin, ¿Are they all dead, broken vessels at the edge of the blinded fountain?). Once again, we have a violent transition, this one asking questions of why violence and fighting seems to be such a constant not only in Mexican history, but in human nature. The writing about war and liberation does not reference any historic event in particular, but rather the multiple periods of unrest in the country. Finally, the pace of the poem slows down, and Paz makes some reflections on what Mexican identity is, and where can we find it. He says that we have to look back and understand that our identity is not fragmented, but actually a combination of pieces that complement each other to make Mexicans who we are today and today, right now, I feel my sweet tooth calling me.

Cacao was one of the most coveted natural resources of the Aztec empire. The original cacao beverage is cold, water based, bitter, and probably spicy (because after death, that’s the second thing that Mexicans are most obsessed with). Without breaking the pattern, the beverage was consumed in special occasions, especially in funerary rites. The beverage was cold, because who in their crazy mind is going to drink something hot in the Mexican valley summer. Besides the cacao, the beverage was prepared with different spices, including chilli powder, for adding that extra kick. When the Spanish arrived in the territory and tried it out, they thought it had potential, so they began their own culinary experiments with Cacao and basically Mexican identity (fractured) and fusion cuisine (also fractured) were born at the same time.

So, I was drinking hot coco about a year ago while spiraling in a deep rabbit hole on YouTube, as one does, and I came across this beautiful animated short film. In it a bunch of tiny creatures that look like pre-Hispanic sculptures run around gathering jade beads to help an Aztec god get dressed. The skin of the little creatures looks like they are made of red clay, which is true for real pre-Hispanic ceramics. The beads that they are collecting are jade, which was probably the most precious stone at that time, and they are using it to dress a god, one that is surrounded by nature and which could very easily be Quetzalcoatl (pronunciation link) all covered in feathers. As I was sipping my colonizer’s drink, I felt that this is Mexico, but it is not at all, the film is actually French.

It is odd to finish a rumination about Mexican identity with a French film, but maybe the French have a point. In all honesty, I don’t know what these examples from a ballet to an album cover might tell us, besides the fact that our identity is all over the place. What all these random interests of mine tell you is that Mexican culture is indescribable. I have learnt to think about it as more of a feeling rather than a tangible thing. The feelings that come when reading a Paz poem, or when listening to Caifanes, and feeling, yes! That is exactly what Mexican identity is! I know it is not the big revelation you might have expected, but it is the way in which I have come to peace with my pieced-together culture. Feelings are the glue holding together my ancestors’ traditions no matter whether they came by boat wearing funny helmets or saw the splendor of Tenochtitlán (pronunciation link) wearing a funny headdress.

I don’t know what else to say, I guess Mexican identity is meant to be this ever-flowing thing that catches influences from all over, and that manages to create a weird balance between the old and the oldest while still being fresh and modern. I never worried too much about all of this until I started seeing it from an outside lens and notice in fact how odd we are and how hard to put into words it is. The only thing that I can say about it, that has not been said by the great artists, writers, and singers of our country, is that no matter how weird our identity might seem, how fractured, how hard to understand, we need to not overthink it and just feel it. Let ourselves float in the broad ocean filled with the shards and fragments of culture that make up the totality of the Mexican soul.

©Renata Blanco and the CCA Arts Review

No comments:

Post a Comment