THE GREAT FEMINIST REVENGE FILMS OF 21ST CENTURY KOREA

The wild women of Korean cinema

By Fiona Xu

South Korea is going through a feminist revolution that is as quiet and subversive as it is radical. It’s a difficult cultural shift to actually pin down. Many aspects of Korean society achieve a real equality between men and women, but there are other aspects that are, how shall we put it, much less progressive. This makes for an interesting and volatile situation and what’s fascinating, besides the cultural and sociological ramifications, is how feminism is represented in art, and especially the movies. Almost any contemporary Korean movie you see will have interesting takes on feminism and women, especially young women. We could literally choose from hundreds, but these three are especially relevant: Park Chan-wook’s Sympathy for Lady Vengeance (2005); Cheol-soo Jang’s Bedevilled(2010) and Cho Nam-Joo’s Kim Ji-young, born in 1982 (2016).

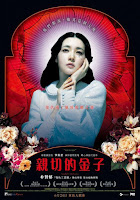

Sympathy for Lady Vengeance is obviously about revenge, you can’t miss it, it’s right in the title. The film asks for us not just to think about revenge, but to have sympathy for it. Park mixes the concept of original sin and feminism, blends them together, and lets them go at it in one wild, crazy tale. Lady Vengeance tells the story of Geum-ja, a beautiful young woman, who is framed by Mr. Baek and is sentenced to 13 years in prison. Geum-ja is kind, honest, and eager to help the people around her. She is loved by her fellow inmates, winning the nickname “kind” Geum-ja. When she asks a favor, no one has the heart to refuse her request. But, after serving her sentence, she becomes a goddess of vengeance.

No longer kind, she changes her angelic appearance— her long hair becomes curly; she starts smoking; and her makeup becomes wilder (red eyeshadow and a pale foundation)—taking on the appearance of revenge. Along with the material and spiritual support of the inmates, Geum-ja begins to implement a step-by-step, carefully planned revenge. Park is aware of Korean and International gender norms and gleefully breaks all of them. For example, after sleeping with a young man, Geum-ja smokes a cigarette, an act usually reserved for men. At the same time, Park lowers the camera, pushing the young man to the side of the frame. The asymmetrical composition highlights the difference in the status of the characters. Geum-ja is in the visually dominant position and firmly in charge, making us think of her in terms of real power.

|

| Lady Vengeance is coming for vengeance |

Park treats the prison Geum-ja lives in as an obvious symbol of the patriarchy and society itself. There are bullies in the prison, and there are also inmates who stay in their place. In negotiating this world, she tries to fulfill the idealized expectations of women in a male-dominated society: understanding; hard-working; always smiling; never angry, like a Madonna. But at the moment she needs help, she is anything but a saint. Geum-ja poisons another prisoner who had been bullying the other inmates. She appears to be helping others, but in fact she is paving the way for her revenge later on.

Lee Young-hae, the actress who plays Geum-ja, was already quite popular throughout Asia for playing the lead in Dae Jang Geum, a role much different from her one here. Park uses this to his advantage, creating a meta-theatrical gap between the actress and the character she plays. By doing so, he lets us see what happens when a woman goes mad. The casting of Lee Young-hae just raises the stakes. We see her new appearance, her new attitude, this incredible transformation, and it is as if Geum-ja’s anger can no longer be contained. It’s an interesting form of feminism and one that directly confronts power.

|

| Revenge isn't easy |

Cheol-soo Jang’s Bedevilled is a woman’s film. The focus is not on revenge like Lady Vengeance, but on the mammoth levels of discrimination that women suffer in real life. The film tells the story of Hae-won, a single woman struggling under intense familial pressure to make money in Seoul's financial industry.When she is forced to take a leave of absence, Hae-won returns to her long-lost hometown, “Nothing Island." It is a beautiful place, but the people are rough, traditional, even barbaric, and believe that women are inferior to men. Hae-won is reunited with her childhood playmate, Kim Bok-nam, a gentle, cheerful, hard-working woman, though Kim's husband and family treat her like a dog, bullying and abusing her at will. Kim wants a better life for her daughter Yeon-hee, but what a woman thinks doesn't matter here. And this is the crux of the film’s version of Korean feminism.

There are many scenes in the movie that deal with the dangers of being a woman controlled by men. For instance, Kim Bok-nam is the only young woman on the island. This makes her a sexual target for every man there. She is subjected to daily domestic abuse and heavy manual labor, while the men on the island (except for the crazy old ones) do almost nothing. One of the interesting side notes of the film is that some of the men on the island are called “breadwinners” for their ability to make money. It’s just how they make money—on the back of women’s labor—that gives the film such a stinging critique of gender norms and power.

|

| Her comes vengeance |

At one point in the movie, Kim Bok-nam tries to escape the island. After she is caught, the men beat her, kick her, and abuse her daughter, Yeon-hee. When Yeon-hee dies, the inconsolable Kim Bok-nam realizes what type of world she has been living in. We always think we are surrounded by friends, and Kim Bok-nam thinks so too. But in this tragedy, this injustice numbs Kim Bok-nam and she takes a sickle—the tool she has worked with every day—and kills the whole village. Like Lady Vengeance, this is a tough form of feminist revenge. If Park Chan-wook's Lady Vengeance tells the story of the rise of women's rights and Bedevilled tells the story of the victim’s revenge, our next and last film, Kim Ji-young, born in 1982, tells the story of the plight of South Korean women in both the home and at work.

|

| Daily life is hard |

Research shows that Kim Ji-young is the most common name for Korean women born in 1982, and director Kim Do-Young’s Kim Ji-young, Born 1982, was by far 2019's most contentious picture. In Korea, it surpassed the hit Joker with 3.6 million views, and the reason why is its depiction of women’s lives and how it resonated with Korean women. A significant portion of the female audience felt that the film was a rare reflection of an ordinary woman, while a large portion of the male audience thought that the film was too focused on putting the blame on men, which they thought to be another kind of prejudice and discrimination.

The main character, Kim Ji Young, is a seemingly ordinary woman who marries at the right age and soon has a daughter, also at the right age. She quits her previous job to become a full-time housewife. After a few years, Kim Ji-young gradually develops a bizarre mental problem where she becomes dazed and confused and seemingly becomes another person. Her illness forces all her relatives, including Kim Ji-young's husband, parents, mother-in-law, and siblings to confront the fact that somehow they and the society around them are making her sick.

|

| There's a lot to handle and it never ends |

The fundamental power of the film is its collection of incredibly realistic stories centered around Kim Ji-young's professional and personal lives. The two most evident factors are the monotony and triviality of child rearing and the prejudice and suffocation women suffer in the workforce. These difficulties are more or less typical for Korean women in both marriage and the workplace and the film is unrelenting in laying these inequities out before the audience.

We see how her life is completely changed by her marriage, the household chores that she has to take on, her obedience to her husband, how much child care costs, the hiring of a nanny, the hassle and trouble of going straight from work to taking care of the children. The film makes clear that this is unpaid work that never goes away. So, that’s the situation of the movie, but it’s her reaction to the situation that makes the movie so potent.

In the film, three different people take possession of Ji Young: her mother, her grandmother, and a friend of her husband’s, Cha Seung Yeon. It’s clear that Ji Young hasn’t actually been possessed, but that these people are aspects of her own subconsciousness. So, what makes the movie so thrilling for Korena women is that Ji Young gets to speak through these people in ways that she never would in real life. It is as if possession is spilling hard-kept secrets.

|

| Who are you? |

The first possession is by her mother, and occurs at her mother-in-law's house. The “mother-possessed” Ji-young says that “Ji-Young” can’t stand her mother-in-law ordering her about and that she needs a break. The mother-in-law is at the top of the power chain in the family. She can discipline her son and not-so-gently guide her daughter-in-law’s life. She is a "beneficiary of patriarchy" and a "defender of the patriarchal family." In the film, Ji-young's mother-in-law demands that Ji-young work and forbids her son to help with any of the household chores. And to top it off, she opposes her son's taking parental leave. In the power structure of mother-in-law and daughter-in-law, Ji-young is powerless to resist and can only voice her demands through the voice of her mother, whose power is comparable to that of her mother-in-law and also understanding of Ji-young’s plight.

The second possession is Ji-young and his wife's mutual college friend—Cha Seung Yeon who died during childbirth. She says Ji-young is distraught and needs to find a job. Unlike the first possession, which has to do with a powerful rival, this possession relies heavily on the tragic warning of a close friend. If Ji-young’s husband does not wake up to his wife’s plight and change the power imbalance between them, perhaps Ji-young will be the next tragedy.

The third possession is Ji-young's grandmother, who recognizes and appreciates the sacrifices Ji-young's mother made for her family and refuses to allow her to make them again for Ji-young. Interestingly, because of the possession, three generations of women share the same body. And three generations of women find solace in that they play the same role - the sacrificial mother—and face the same dilemma, the inability to realize themselves. This is the most powerful possession because it not only includes three generations of Korean women, but also potentially all Korean women.

|

| Things look fine, but... |

The three possessions, although ostensibly spoken by different characters in different situations through the mouth of Kim Ji-young, are clearly Ji-young herself, what Ji-young wants to say but cannot. The plight of the aphasic woman stems from a sense of powerlessness in the face of a hierarchical gender. And possession becomes another way of speaking for her and with her.

Since the late 1980s, Korean films have featured more and more female characters until the mid-1990s. After the 1997 economic crisis, misogyny grew, and cinema plots returned to centering around male characters. But now, Korean films today commonly feature some aspects of feminism. In 2019, 22 women directed 169 Korean films. Actresses starred in 12 out of 22 films directed by women in 2019. 48 of 147 films directed by men starred women, or 32.7%. Still, only eight (18.6%) of the commercial films made in South Korea in 2019 and 6 (15%) in 2018 had an actress in first or second position in the cast list. Few Korean films have multiple female leads, but 28 had dual male leads in 2019. Things are changing, but it is a fitful change, although with much hope and promise for the future.

The rise of Korean cinema is as remarkable as its beauty. Since the post-war era, Korea, which has a legacy of "machismo," has been impacted by Western civilization. Feminist consciousness and feminism have risen significantly in Korea, and this is reflected in films. Korean films are now increasingly feminist. For Korea, the resistance of the younger generation of women is just beginning, and the feminist movement is a work in progress at the moment. In general, Korean films today reflect on the moral tradition of male superiority over women, and they are permeated with thoughts on the status of women, their roles, femininity, and gender relations.

©Fiona Xu and the CCA Arts Review

No comments:

Post a Comment